My new website is finally up and running. Check it out at kristinethornley.com

(Note: you may have to delete cookies or clear your cache if the old one is still visible.)

My new website is finally up and running. Check it out at kristinethornley.com

(Note: you may have to delete cookies or clear your cache if the old one is still visible.)

Copy editing medical content requires a basic knowledge of medical terminology or the “language of medicine.” It is the medical copy editor’s job to ensure that the right terms are used and that they are spelled correctly. There is a big difference between a colonoscopy and a colostomy—and you do not want to be the one to mix them up. You will be a more effective and efficient medical copy editor with a good foundation in medical terminology.

Copy editing medical content requires a basic knowledge of medical terminology or the “language of medicine.” It is the medical copy editor’s job to ensure that the right terms are used and that they are spelled correctly. There is a big difference between a colonoscopy and a colostomy—and you do not want to be the one to mix them up. You will be a more effective and efficient medical copy editor with a good foundation in medical terminology.

Body’s Systems and Basic Physiology

Understanding medical terminology starts with knowing the body’s systems and the parts that comprise them (skeletal, muscular, integumentary, cardiovascular, lymphatic, respiratory, gastrointestinal, endocrine, nervous, urinary, and reproductive) as well as some basic physiology. If you do not have a biology background, the Khan Academy offers free online courses in human anatomy and physiology. InnerBody is a free virtual human anatomy website that offers hundreds of interactive anatomy pictures and system descriptions. Or perhaps you would like to take a “peek under the hood” with Anatomy & Physiology For Dummies.

Understanding medical terminology starts with knowing the body’s systems and the parts that comprise them (skeletal, muscular, integumentary, cardiovascular, lymphatic, respiratory, gastrointestinal, endocrine, nervous, urinary, and reproductive) as well as some basic physiology. If you do not have a biology background, the Khan Academy offers free online courses in human anatomy and physiology. InnerBody is a free virtual human anatomy website that offers hundreds of interactive anatomy pictures and system descriptions. Or perhaps you would like to take a “peek under the hood” with Anatomy & Physiology For Dummies.

Common Medical Terms and Medical Root Words

You need to be familiar with common medical terms and medical root words. Most common medical terms used today are derived from Latin or Greek, which makes sense since the Greeks were the founders of modern medicine. Having some knowledge of the Latin and Greek bases of words will go a long way to understanding the word and ensuring that it is used correctly. For example, the Greek roots myo (muscle) and myelo (bone marrow) look similar but have very different meanings. I was fortunate to take a “Latin and Greek for Scientists” course in undergrad, but I suspect that many of you with a natural love for language will already have some knowledge in this area. As a starting point, here is a list of medical roots, suffixes, and prefixes with their meanings and etymology. For medical terms, the Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy is the most widely used comprehensive medical textbook for both professionals and consumers (available in print, online, and as an app). The American Medical Writers Association also offers a self-study workbook on Elements of Medical Terminology that is designed primarily for those with little or no medical background. You do not have to be a member to purchase it.

You need to be familiar with common medical terms and medical root words. Most common medical terms used today are derived from Latin or Greek, which makes sense since the Greeks were the founders of modern medicine. Having some knowledge of the Latin and Greek bases of words will go a long way to understanding the word and ensuring that it is used correctly. For example, the Greek roots myo (muscle) and myelo (bone marrow) look similar but have very different meanings. I was fortunate to take a “Latin and Greek for Scientists” course in undergrad, but I suspect that many of you with a natural love for language will already have some knowledge in this area. As a starting point, here is a list of medical roots, suffixes, and prefixes with their meanings and etymology. For medical terms, the Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy is the most widely used comprehensive medical textbook for both professionals and consumers (available in print, online, and as an app). The American Medical Writers Association also offers a self-study workbook on Elements of Medical Terminology that is designed primarily for those with little or no medical background. You do not have to be a member to purchase it.

Correct Spelling and Common Errors

The field of medicine is filled with ridiculously complicated terms, such as sphenopalatine ganglioneuralgia (“ice cream headache”) and unusual spellings (eg, hemorrhoid, diphtheria). You are definitely going to need a medical dictionary. Stedman’s Medical Dictionary is the authoritative spelling resource for more than 54,000 medical terms and it is available in print, online, and as an app. Stedman’s also offers a medical/pharmaceutical spellchecker that is compatible with many word processing systems. Windows users also receive a universal spellchecker that integrates medical and pharmaceutical spellchecking throughout the entire desktop, not just in Word. This is an invaluable tool for medical copy editors.

The field of medicine is filled with ridiculously complicated terms, such as sphenopalatine ganglioneuralgia (“ice cream headache”) and unusual spellings (eg, hemorrhoid, diphtheria). You are definitely going to need a medical dictionary. Stedman’s Medical Dictionary is the authoritative spelling resource for more than 54,000 medical terms and it is available in print, online, and as an app. Stedman’s also offers a medical/pharmaceutical spellchecker that is compatible with many word processing systems. Windows users also receive a universal spellchecker that integrates medical and pharmaceutical spellchecking throughout the entire desktop, not just in Word. This is an invaluable tool for medical copy editors.

I will discuss abbreviations and word usage in medical writing in future posts. Until then, happy adventures in editing!

Many authors who contact me think that proofreading is synonymous with copy editing (and sometimes copy editing is synonymous with copy writing, but that’s a different story). But copy editing and proofreading are two different processes done at two different stages of production. When I explain to an author who is clearly looking for copy editing that proofreading is actually the final step after typesetting and layout, I still have many who say that is what they need because they have already put their manuscript in final publishing format—without having copy edited the text first. Editors can understand how eager authors are to see their manuscript “look” like a book, but there are stages that should be followed so that you do not end up wasting valuable time and money.

According to the Professional Editorial Standards of Editors Canada, copy editing is defined as “editing to ensure correctness, accuracy, consistency, and completeness,” whereas proofreading is “examining material after layout or in its final format to correct errors in textual and visual elements.”

Science or Art?

Regarding the text, it has been said that proofreading is a science, editing is an art. Proofreading is correcting text. Copy editing is not just correcting, it is also improving. Let’s take a look at the following example:

| Original sentence: | I would like to take the oportunity to think you for agreing to met with me on Monday, May 21st. |

| Proofread correction: | I would like to take this opportunity to thank you for agreeing to meet with me on Monday, May 21. |

| Copy edited correction: | Thank you for agreeing to meet with me on Monday, May 21. |

Notice the difference. In the proofread correction, the text remained the same, but the spelling and number errors were fixed. In the copy edited correction, the wordiness of the sentence was corrected. This change in wording makes it a “stronger” sentence. The proofreader would not change the wording. As long as it is understandable, the proofreader would leave it as it is and fix the copy editing and layout errors only.

When, Where, and How

Copy editing and proofreading differ in when, where, and how they are done. The copy editor works on the manuscript before layout, usually on-screen in a Word document. This is a much easier time and location to copy edit. The copy editor can adjust the font size and line spacing of the document for easier reading without worrying about messing up the layout. The copy editor also has access to lots of built-in Word functions as well as add-in Word tools and macros to help in the process. The proofreader, on the other hand, works on proofs of the final manuscript after layout, usually within a PDF or on a hard copy (printed out version). Space to work is far more limited in this format and the proofreader reviews things that the copy editor never sees, such as all the style and visual elements, cross-references and running heads, typography and page formatting.

| Copy editing (manuscript in a Word document) |

|

| Proofreading (PDF proof of page spread) |

|

How are corrections marked? When copy editing a Word document, track changes is used to mark errors and changes to the text. Errors and text changes are marked directly within the body of the text. Comments are usually made within the margins. In proofreading, however, changes have to be indicated in two places: within the body of the text using standard symbols and a corresponding symbol or note/query in the margin on the same line so that the error can be easily spotted. A summary of the differences is presented below:

| Copy Editing | Proofreading |

|

|

My favourite quote describing the differences between copy editing and proofreading comes from Suzanne Gilad in Copyediting & Proofreading for Dummies:

“If publishing were like getting dressed in the morning, the copyeditor would review the chosen outfit, bearing in mind the weather and what the day’s agenda entails. She may decide on different shoes or a wider belt. She may pick out a different jacket. She may even suggest an entire wardrobe change. She examines the overall appearance and makes suggestions to create the nicest-looking ensemble that ever stood in front of the bedroom mirror. The proofreader then waltzes in and points out the deodorant marks on the shirt.”

What other differences are there between copy editing and proofreading? Share them with us.

Happy Adventures in Editing!

Kristine

References often do not get the attention that these important manuscript elements deserve. Scientific and medical journal articles use references to support the authors’ hypotheses, to credit or acknowledge the work of others, and to direct the reader to additional information or resources. The role of the copy editor is to ensure that all references listed are actually cited within the paper, are complete and accurate, and are presented in the correct format and style used by the journal. Frankly, it can be pretty tedious. But, before we explore some time-saving tips, let’s review the basics.

Print Journal Articles

As per the AMA Manual of Style guidelines, a complete print journal reference should include:

The basic style for a citing a print journal article:

Here are some example print journal article references (recognize any names?):

Electronic Journal Articles

In this digital age, references are now so much easier to access. Unfortunately, an online presence can be much more transient than print. Links break over time, long uniform resource locators (URLs) are prone to typographical errors (and wreak havoc with typesetting!), and websites can be updated repeatedly so there may be many different versions of the same article. For these reasons, it is important for the author to try to capture all relevant information about an online reference at the time it was accessed. At minimum, this requires the URL and date of access.

The sample format is:

Some examples:

Some points to remember about citing URLs:

Electronic Document Identification Systems

Because URLs can break, change, or disappear altogether, many publishers now require more stable identifiers of online material. Two methods are commonly used: the Digital Object Identifier System and the PubMed Identification Number System. A number of journals that I work for use these identifiers to pull references directly and automatically populate the reference list with the correct information in the correct format (such a time saver!).

Digital Object Identifier System

The DOI System was first launched by the International DOI Foundation in 2000. The goal is to provide an “actionable, interoperable, and persistent” digital network identifier used by publishers and other sectors, such as science data centres and movie studios. In 2012, the DOI System was adopted as the International Standard (ISO 26324). They provide a Digital Identifier of an Object (an object can be any physical, digital, or abstract thing). Over 100 million DOIs have been assigned through a federation of Registration Agencies worldwide with an annual growth rate of 16%.

There are 2 elements to a DOI: the prefix and the suffix (separated by a forward slash). All DOIs begin with 10 and are of variable lengths, but they never change once they are assigned. For example, the DOI 10.1183/09031936.02.00088702 for the article listed below begins with “10” like all DOIs, “1183” is the prefix that was assigned by the DOI Registration Agency, and “09031936.02.00088702” is the suffix. Readers can type or paste the DOI name (including the 10 at the beginning and all numbers before and after the slash, but excluding extra characters and sentence punctuation marks) at the DOI website (http://dx.doi.org/). If you have the DOI, you do not have to provide the URL or accessed date in the reference. The DOI appears as the last item in the reference immediately after “doi:” and is set closed up (i.e., no space between):

PubMed Identifier System

For journals indexed by PubMed and part of a PubMed citation, a unique PubMed identifier (PMID) is assigned. Readers can enter the PMID in the search box on the PubMed website (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/) to find the article. The PMID is not usually included in the reference citation like the DOI is, but rather is used as a “behind-the-scenes” identifier or as a link. For example, the PMID for the following article is 10806140 and is used as a link to PubMed website:

Final Notes

Remember that these electronic identification numbers are only identifiers—they do not provide any information regarding quality of the content or the type of paper identified. They are only there to try to locate a specific article or work in an endless sea of digital information.

Even in this age when text is often reduced down to 140 characters or less, don’t forget the punctuation. It just could save a life!

We recently went to visit our boys at their summer camp. While driving near Algonquin Provincial Park, I saw a handmade sign posted on a front lawn that read “Slow Kids Crossing.” I was so distracted by the sign (do they mean their kids are physically or mentally slow?) that I could have accidentally hit someone. It is safe to assume they intended “Slow, Kids Crossing” (or “Slow Down, Kids Crossing” would have been better), but this example goes to show the power of punctuation.

The lack of punctuation in this sign obscured the intended meaning. For those of us who notice this sort of thing, it can be annoying—and sometimes amusing. Lynne Truss, author of Eats, Shoots & Leaves: The Zero Tolerance Approach to Punctuation, says: “We are like the little boy in The Sixth Sense who can see dead people, except that we see can see dead punctuation.”

The comma is especially complicated because it plays a grammar role, but also a role as an indicator of the rhythm and flow of the sentence. It is also the most controversial punctuation mark. People have very strong opinions about the Oxford (or serial) comma, but I will leave that heated topic for another post (there has already been enough bloodshed).

The comma indicates a slight break between different parts of a sentence. The function of the comma is to group together words, phrases, and clauses to make a sentence clearer to read. The effect of a misplaced or omitted comma can be quite comical at times. Here are some examples from 25 Biggest Comma Fails on BuzzFeed:

Many people use the comma incorrectly. They either omit it or go crazy with the comma. Read on for a quick primer in correct comma usage.

I hope you learned something from this very general introduction to using the comma. Stay tuned for a separate post in which I will discuss the use of the comma in lists.

Happy Adventures in Editing!

In my last post, I discussed the results of a recent study that found our sedentary editing and writing jobs increase our risk for some cancers. In part two, I offer some tips that may just save your life (I like to think so anyway).

Move during the day

“Sitting is the new smoking,” says Brigid Dineen, Life Coach, yoga instructor, and organizer for the Yogapalooza festival in Toronto. “Although you can’t quit sitting, you can take action to minimize its consequences on your health and well-being.”

Brigid suggests we take a break and get moving at least once an hour. “It will help to improve your posture, your circulation, your stress levels and mood, and your mental focus. You will also reduce your risk of back pain, weight gain and becoming a ‘zombie’ from staring at the screen for too long.”

Any activity will do. Take a walk, do some stretches, or—Brigid’s favorite—take a dance break! Be intentional about taking a break or the day will get away from you (even set a timer to remind you). Here are some great options:

Get your vitamin D

Vitamin D deficiency may be the biological pathway through which excessive sitting increases cancer risk. If you can’t get outside during the day for a walk to catch some natural vitamin D, take a supplement.

Be more active outside work hours

Sitting risk is cumulative. If you work at a desk all day and spend your evenings sitting on the couch watching TV, you are in real trouble. Spend your leisure time being more active. Take a walk. Take up a sport. Learn ballroom dancing. Just get moving!

For your workspace

Some people like to use a standing desk or sit on an exercise ball while working. Even just placing your garbage can or printer on the other side of the room will help because you will have to get up to use them during the day.

Tell us, what do you do to break up your sitting time during the day?

I never considered editing a dangerous job. In fact, editing fulfilled all my safe job criteria: it involved a lot of sitting and could be done in my pajamas. The only danger was an occasional coffee spill. New research finds sedentary desk jobs, such as writing or editing, can increase our risk for cancer—and even exercising every day does not reduce this risk.

I never considered editing a dangerous job. In fact, editing fulfilled all my safe job criteria: it involved a lot of sitting and could be done in my pajamas. The only danger was an occasional coffee spill. New research finds sedentary desk jobs, such as writing or editing, can increase our risk for cancer—and even exercising every day does not reduce this risk.

Sitting is the new smoking

Excessive sitting has already been found to increase our risk of obesity as well as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension and even depression. According to a recent meta-analysis of 43 observational studies that included over 4 million individuals and 68,936 cancer cases, increased sitting time each day also increases our chance of colon, endometrial and lung cancers. In addition, each two-hour per day increase in sedentary time was related to a statistically significant 8% and 10% increase in colon cancer and endometrial cancer risk, respectively (a 6% increased risk of lung cancer was borderline significant).

Several mechanisms were suggested including increased weight gain and obesity, vitamin D deficiency, and inflammatory responses triggered within the body.

All sitting is not created equal

Sitting watching TV was found to more detrimental than occupational sitting. Another prospective study reported that each two-hour per day increase in TV time was associated with a 23% increased risk of obesity, but only a 5% increased obesity risk for sitting at work time. The authors suggest that this is because we are more likely to snack on unhealthy food while watching TV.

Exercise isn’t enough

Perhaps even more concerning was that adjusting for exercise did not affect the positive association between sedentary behavior and cancer in this most recent study. This means that the increased cancer risk is not just due to inactivity and that exercising after sitting all day isn’t enough to counteract this risk. It is like thinking that going for a jog will make up for smoking a pack of cigarettes a day.

But wait—you don’t need to change careers! Read part two to find ways to lessen your risk.

“Too many cooks spoil the broth” –English proverb

Toda y’s adventure in editing was an “offer” I had not seen since I first started out in editing. An author wanted me to edit a chapter of his book—for free (“it was only one chapter”). Presumably as many editors as he had chapters in his book were also contacted with this deal. His goal was to end up with an edited book for nothing. Almost every editor has been approached with this scam at some point during their career. Sometimes we are offered a pittance; sometimes we are promised “great exposure.”

y’s adventure in editing was an “offer” I had not seen since I first started out in editing. An author wanted me to edit a chapter of his book—for free (“it was only one chapter”). Presumably as many editors as he had chapters in his book were also contacted with this deal. His goal was to end up with an edited book for nothing. Almost every editor has been approached with this scam at some point during their career. Sometimes we are offered a pittance; sometimes we are promised “great exposure.”

“Next time I go grocery shopping,” said fellow editor Katherine Barber, “I’m going to say, ‘Hey Loblaws, give me my groceries for nothing and I’ll tell all my friends on Facebook and Twitter how wonderful you are’.”

You wouldn’t do it with your grocery store—it is just as inappropriate when dealing with a professional editor.

It is usually an inexperienced author who tries this, one who does not understand the role or the value of an editor. One of the primary goals of editing is consistency, consistency, consistency. How do you achieve this with a dozen different editors?

Yes, editing can be expensive (it is a professional service after all). If you truly think you have “probably the greatest story ever written” (actual quote), don’t shortchange your work by farming it out in small chunks to many different editors in an effort to save money. You might actually have the greatest story idea ever, but if you are an inexperienced writer it takes a lot of work—by you and your editor—to get it to greatest story level.

How can you afford an editor? You are creative—think creatively! But be sure to discuss your proposal with your editor before editing begins. After you receive the invoice is not the time to propose your idea. Here are some suggestions to get you started (with many thanks to the members of the Editors’ Association of Earth Facebook group for their wonderful recommendations and anecdotes).

Barter

Everyone has something to offer and many editors are open to bartering. The EAE editors have received bottles of wine (what wouldn’t I do for some bottles of wine?), pieces of art, laundry or grocery delivery, meals, or services such as house painting or installing carpet. Remember that bartering is still counted as income and subject to tax (editors will have to issue a receipt with an equivalent dollar amount and submit at tax time).

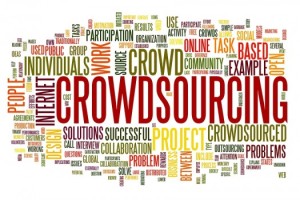

Crowdfund

Crowdsourcing is splitting a large task up into very small projects that are completed by many different people. Instead of splitting up the job into pieces, split the cost of hiring a good editor. Crowdfunding is raising money through small contributions from a large number of people via the Internet and social media. Pubslush is a crowdfunding platform specifically for authors, but there are many other crowdfunding sites, such as Indiegogo and Kickstarter. You could offer contributors a signed copy of your book once published, a chance to name a character, or an acknowledgement within the book.

Hire a recent grad

It is very difficult for a new editor just starting out to establish themselves and generate clients. A recent grad from a publishing program may be willing to do the project for less money to build their project list. They should have formal editing training. You want them to have the skills—they just may not be as quick as a more experienced editor. The Publishing program at Ryerson University in Toronto (where I studied publishing) offers a job announcement service for grads. You can contact them with the details of your project and they will distribute your job posting to current students and alumni free of charge. Check your local universities for a similar service if you live outside the Toronto area.

Do the work yourself

Maybe hiring an editor is completely out of the question for you financially. There are many books out there that can teach you the basics. It just takes an investment of your time—and a library card. The bonus is that you now will have these self-editing skills for your next project. Here are some of my favourites:

Get a little help from your friends

Have as many people as possible—your spouse, friends, relatives, the guy down the street—read your manuscript and provide feedback. This is a good start, but know that because these people have a relationship with you, their feedback is going to be censored somewhat. As famous editor Alan D. Williams has said, “An editor [does] something that almost no friend, relative, or even spouse is qualified or willing to do, namely to read every line with care, to comment in detail with absolute candor, and to suggest changes where they seem desirable, or even essential. In doing this the editor is acting as the first truly disinterested reader, giving the author not only constructive help but also, one hopes, the first inkling of how reviewers, readers, and the marketplace…will react, so that the author can revise accordingly.” You do need unbiased eyes to assess your work, so another option is to join a writers’ group or writing circle. They are all writers and committed to writing. Their input could be invaluable. But it is not a one-way street. You will be expected to help with other writers’ works too. Check your local library for a group that meets face-to-face or check the Web for online writing groups, such as Scribophile.

Share some of your creative ideas or your past experiences.

Happy Adventures in Editing!

P.S. Make sure to visit Katherine’s Wordlady blog too—it is wonderful.

For a recent clas s in Advanced Writing for Health Communicators, we had to compare the websites of the Boston Ballet and the Boston Red Sox. The Boston Ballet website is sophisticated, formal, and elegant; the Red Sox website is bright, energetic, and busy. The writing and the readability of the websites are also very different indicating that they are purposefully trying to reach very different audiences. So what exactly is readability and how can you gauge the readability of your own documents? Read on to learn more.

s in Advanced Writing for Health Communicators, we had to compare the websites of the Boston Ballet and the Boston Red Sox. The Boston Ballet website is sophisticated, formal, and elegant; the Red Sox website is bright, energetic, and busy. The writing and the readability of the websites are also very different indicating that they are purposefully trying to reach very different audiences. So what exactly is readability and how can you gauge the readability of your own documents? Read on to learn more.

Readability and readability tests

Readability is the ease with which your writing can be read. Readability tests are mathematical calculations typically based on the difficulty of the words used (i.e., the average number of syllables per word) and the difficulty of the sentences (i.e., the average sentence length). For this article, I will discuss only the ones that are freely available and built into Microsoft Word.

Pros and cons of readability tests

Readability tests are only predictions—they are not the definitive measure of how good your writing is. They should be used as a quick assessment during the writing/revision process. As Cheryl Stephens writes in her article All About Readability, readability tests cannot measure reader interest or enjoyment. They also cannot measure if your content is presented in a logical order, how well complex ideas are presented, or if your vocabulary is appropriate. Readability tests are best used as a screening device and they should not be the only tool you use for assessing your text. They are also good for gauging improvement in your writing if you are trying to learn how to write more clearly because they provide a quantitative number for comparison.

Comparing ballet and baseball

For my class, I compared the readability stats of the history page of the Boston Ballet website and the 2010s history timeline of the Red Sox website. In Microsoft Word, the readability statistics are available in the Review toolbar under Spelling and Grammar. You may need to make sure that “Check grammar with spelling” is checked under Proofing in the Options menu first.

The Ballet site had more words per sentence and more characters per word than the Red Sox site (i.e., used bigger words and longer sentences). Readability testing results are listed below:

| Readability measure | Ballet | Red Sox |

| Passive sentences | 5% | 12% |

| Flesch Reading Ease | 19.6 | 51.5 |

| Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level | 16.4 | 10.7 |

Passive sentences

The test simply finds the percentage of sentences in the document that are written in the passive voice. For writing in plain language, one of the first tips is to write in the active vs. the passive voice. In the active voice, the subject does the acting (e.g., the cat chased the dog); in the passive, the subject is acted on (e.g., the dog was chased by the cat). (I use these examples because that is the way it happens in my house.) Passive sentences flip around the sequence and natural order of the sentence and are more difficult to read. There is no strict guideline, except try to keep it as low as possible. Greater than 5% would be too high for plain writing. Surprisingly, the Red Sox site not only had more passive sentences than the Ballet site, but at 12%, it was well above an appropriate level. Not only are active sentences easier to read, they have more energy, which is exactly what they should be going for on the Red Sox site. I expected that the proportion of passive sentences would have been higher for the Ballet site—the fact that it is not shows that they had a good writer.

Flesch Reading Ease

The Flesch Reading Ease test rates text on a 100-point scale. The higher the score, the easier it is to understand the document. For most standard documents for a general audience, the score should be between 60 and 70. Neither the Ballet or Red Sox site made this cutoff (19.6 and 51.5, respectively), but the Ballet website was definitely low indicating that they were not even attempting to reach a “general” audience. The Red Sox site is obviously trying to reach this general audience but missed the mark.

Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level

The Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level test rates text on a U.S. school grade level (e.g., a score of 8.0 means that an eighth grader can understand the document). Most documents for a general audience should score between 7.0 to 8.0. Again, both websites scored outside of this ideal range for a general audience. The Red Sox site read at a grade 10 level and the Ballet site read at a senior year in university level. The Ballet site appears to be focusing on people who are university/college-educated (and who potentially have money and will buy tickets and/or donate) and the Red Sox site is geared toward those with a lower high school education.

The takeaway from these tests is that both websites are trying to reach a different audience with their writing, although the Red Sox site was the less successful of the two. The Red Sox site should be geared toward a more general audience; therefore, the passive sentences should be at a minimum, the Flesch Reading Ease test score should be well about 60, and the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level needs to drop a few years.

Other methods of testing readability

Here are some other suggestions for testing and improving the readability of your work:

Identify your audience

The most important thing you can do to make sure that you are reaching your audience is to determine who your audience is. Before you even start writing, ask yourself:

If you can answer these questions and keep these answers in mind while writing, you will go a long way toward reaching the audience you intend to reach.

The question came up today about when to use who versus whom. Let us seek the answer from The Oatmeal. They provide far more entertaining answers to grammar questions than I could offer (I am just not that inspired by the apostrophe). Check out the links below. Do you agree? Is the semicolon the most-feared punctuation on Earth?